Mini Theaters Fuel Diversity and Expand the Filmmaker and Audience Base

Films need to be seen by audiences before they can come into existence and go out into the world. Over the past decade, over 1,000 films have been released each year in Japan (959 films in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic!). About 600 Japanese films get released each year and in actuality many more films are being made, and they crowd roughly 3,600 screens.

This profusion of films is sustained by independent “mini theaters” like Eurospace (opened in 1982) in Shibuya, Tokyo. Forty percent of the films released are screened exclusively in mini theaters. These theaters have conveyed large benefits on Japanese films produced and released outside of the major studios and the commercial film industry. Mini theaters expand the base of filmmakers and audiences and fuel the diversity of cinema in Japan.

Mini theaters emerged in the 1970s when the Japanese film industry was in decline. Film studios that once nurtured directors shrank their production pipelines, and filmmakers of diverse provenances emerged. Mini theaters actively screened individualistic films that the major studios hesitated to pick up.

In the late 1980s, Hara Kazuo’s “The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On” (1987) became a sleeper hit at Eurospace and elevated the box office clout of documentary film. Tsukamoto Shinya’s self-produced “Tetsuo: The Iron Man” (1989) took off after a late-show opening at Nakano Musashinokan (closed in 2004). Sakamoto Junji’s “Dotsuitarunen” (1989) set up its own theater. It was the ultimate mini theater exclusive.

During the halcyon 1990s, it seemed like all the interesting Japanese films were at mini theaters. Feature film debuts from directors who went on to great success include “Maboroshi” (1995, dir. Kore-eda Hirokazu) at Cine Amuse East & West (renamed Human Trust Cinema Bunka Dori in 2008, closed in 2009) and “Suzaku” (1997, dir. Kawase Naomi) at Ginza Theatre Seiyu (renamed Ginza Theatre Cinema in 2000, closed in 2013). Films like “Kichiku Dai Enkai” (1997, dir. Kumakiri Kazuyoshi) screened at Eurospace and won awards at the Pia Film Festival. Without mini theaters, these films wouldn’t have reached the world.

At the turn of the new century, movie theaters became cinema complexes while digitalization transformed the film industry landscape. Quirky films waned as cinema complexes went for hits and audiences flocked to popular movies. Meanwhile, huge numbers of indie films were produced as filmmaking became more attainable with the increasing ease of high-end film production.

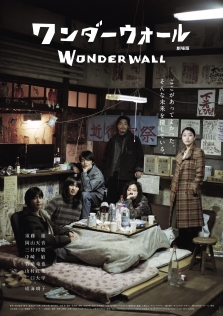

Although some mini theaters have closed down, they still serve as rescue operations for independent cinema. Ikebukuro Cinema Rosa took in “8000 Miles” (2009, dir. Irie Yu), and “Saudade” (2011, dir. Tomita Katsuya) took off from Eurospace. The hit film “One Cut of the Dead” (2017, dir. Ueda Shinichiro) took in 3.5 billion yen after getting its start at K’s cinema in Shinjuku.

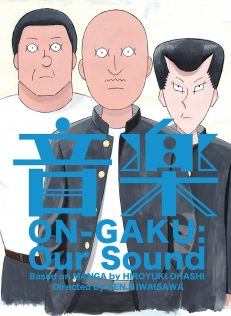

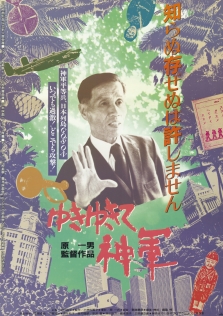

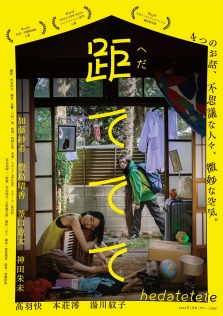

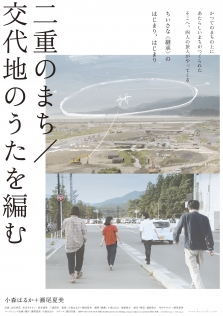

Mini theaters continue to persevere, undaunted by the damage wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. Shinjuku Musashinokan put the spotlight on the indie animated film “On-Gaku: Our Sound” (2000, dir. Iwaisawa Kenji) and Human Trust Cinema Shibuya discovered “Come and Go” (2021, dir. Lim Kah Wai). Many filmgoers concurred when veteran director Takahashi Banmei challenged society with a nationwide mini theater release for his film “No Place to Go” (2022). Without mini theaters, there is no cinema culture in Japan.